Osiyo,

The Cherokee Nation’s story contains more than our fair share of chapters where we struggled for survival. And yet with the support and sympathy from our allies, we continue to persist. We’ve faced forced removal from ancestral lands, health crises, loss of land and the power to self-govern, as well as a hostile federal government time and again.

More importantly, our history overflows with stories about finding strength and resolve within ourselves and our neighbors. In our darkest hours, we leaned into our intellect. We relied on diplomacy against harrowing odds and prevailed, creating one of the world’s greatest democracies in the process.

To build and maintain our democracy, we wielded the power of the written word, shaping our destiny through communication and rhetoric. We dared the United States to live up to its highest ideals while drafting our own. The development of Sequoyah's Cherokee syllabary played a critical role in the advancement of our ability to communicate and remains a cornerstone of Cherokee culture.

Journalism is an important aspect of free-speech exercise. It works alongside our three-branched government as a counterpart to our system of checks and balances. The free press, often referred to as the fourth branch of government, is core to our Cherokee story. As we coalesced into a governmental institution, so did the Cherokee press.

The Cherokee Phoenix was the first Native American language newspaper in the U.S., first printed in 1828. Through communication afforded by the Phoenix’s circulation, we fought against removal. The Phoenix, which in 1829 was called the Cherokee Phoenix and Indians’ Advocate, became a target of the government to disrupt our sovereignty. It wouldn’t be the last time.

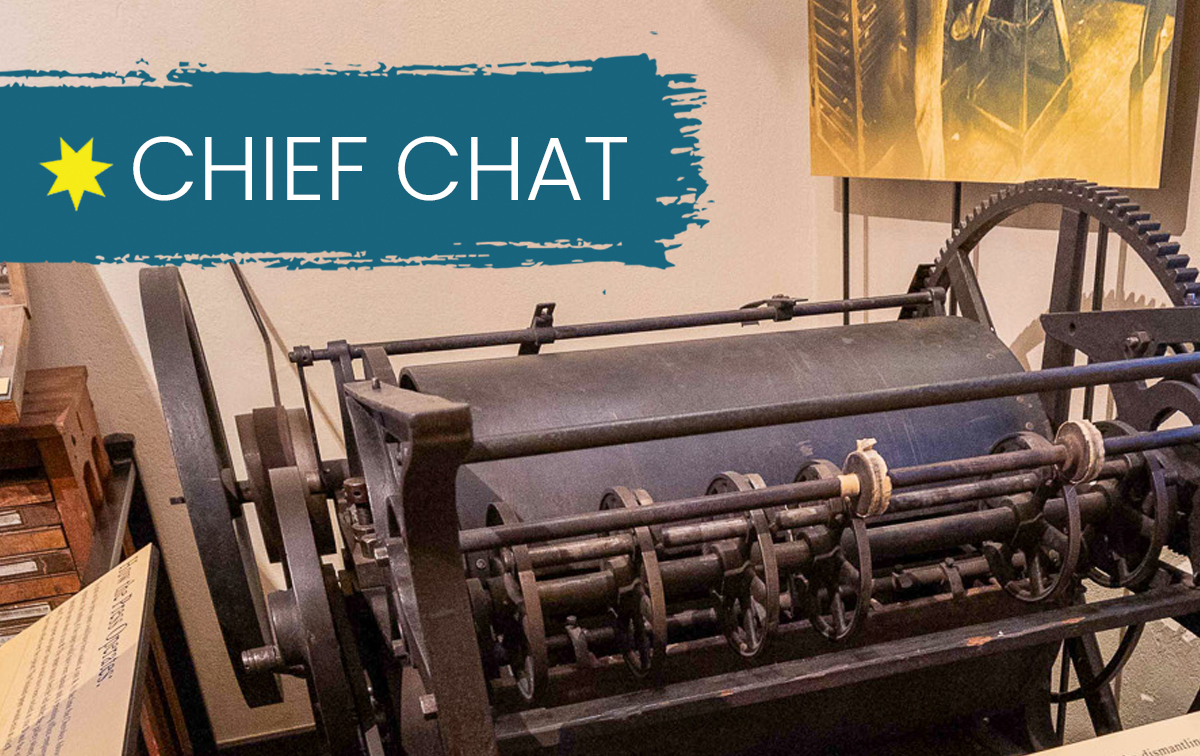

The Phoenix closed in 1834, and that printing press was seized by the Georgia Guard. Although the federal government won for a dark period, Cherokee journalism lived on, reforming in Cherokee Nation’s new homelands. A new physical press took on the important work and printed the Cherokee Advocate from 1844 to 1906.

Tragically, history repeated itself. The federal government again targeted our exercise of free expression and shuttered the Cherokee Advocate, ordering the press to be sold.

The press – the workhorse that our people relied on for mass communication – was lost to us for more than a century. While the Cherokee Advocate and, later, Cherokee Phoenix would prevail again later in the 20th century, we could only admire from a distance one of the most critical tools our ancestors harnessed in those turbulent pre-statehood days. That changed this week.

Along with incredible friends at the city of Tulsa and its Gilcrease Museum collection, we celebrated the return of one our most powerful instruments of communication – now wholly owned by Cherokee Nation and its citizens.

For those who have visited the Cherokee National Supreme Court Museum, the Cherokee Advocate press has been a featured exhibit for years. However, it was on long-term loan from Gilcrease Museum, which acquired the press as a part of its world-renowned American art and artifacts collection.

In many ways, Gilcrease Museum preserved this significant cultural artifact, and we are grateful for good neighbors. Last month, the Tulsa Parks Board voted to return ownership of the press to the Cherokee Nation, an act of voluntary repatriation that we deeply appreciate.

This gesture came amid an active dialogue we have begun across the nation and world as part of the Cherokee Nation Repatriation Project. The goal of the project is to restore historical and cultural belongings to Cherokee Nation. Core to this project is partnering with the organizations that hold these significant items to ensure they are returned in a culturally appropriate and mutually beneficial manner.

We have been working with the U.S. National Park Service that administers the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act on recent improvements to that critical piece of legislation. Enacted in 1990, new rules were recently issued following a 2022 review of which we participated.

The act, also known as NAGPRA, now requires museums and organizations to obtain informed consent prior to displaying or researching human remains or cultural items that fall under its purview. It also requires museums to communicate inventories and strengthens the authority of tribes in the repatriation process. The act allows museums five years to comply with the new rules, and Cherokee Nation stands ready to receive these important items.

One example comes from Harvard University’s Peabody Museum. In 2022, the museum issued an apology and pledged to return hair samples taken from 700 Native American children forced to attend government-run boarding schools. We are currently working with Harvard to recover and appropriately return these remains.

These new rules are critical to ensuring precious artifacts and remains are not lost, discarded or otherwise inappropriately conveyed when returned to rightful owners. Gilcrease Museum and its beneficiaries – the residents of Tulsa – stand as a strong example for organizations across the world.

Our artifacts, our hair and our bones are not novelties for display without permission or regard for our story. We look forward to working with many more organizations in the coming years to protect our storied past.

Wado,

Chuck Hoskin Jr.

Principal Chief